I’m often asked how I got into web development, especially from people that haven’t met many women in the field. Other times it’s people with little kids and they are asking for guidance about how to steer them into programming. I promised them that I would write a long post about it at some point, and now that I’m in the verge of some big changes in my life, I’ve started reflecting on the fascinating journey that got me here.

Rebecca Murphey wrote something similar a while back (albeit much shorter and less detailed), and I think it would be nice if more people in the field started posting their stories, especially women. I sure would find them interesting and if you give it a shot, you’ll see it’s quite enjoyable too. I sure had a blast writing this, although it was a bit hard to hit the “Publish” button afterwards.

Keep in mind that this is just my personal story (perhaps in excruciating detail). I’m not going to attempt to give any advice, and I’m not suggesting that my path was ideal. I’ve regretted some of my decisions myself, whereas some others proved to be great, although they seemed like failures at the time. I think I was quite lucky in how certain things turned out and I thank the Flying Spaghetti Monster daily for them.

Warning: This is going to be a very long read (over 3000 words) and there is no tl;dr.

I was born on June 13th, 1986. I grew up in a Greek island called Lesbos (yes, the island where the word “lesbian” comes from, in case you were wondering), in the small town of Kalloni. I didn’t have a computer as a kid, but I always loved making things. I had no siblings, so my childhood was mostly spent playing solitarily with paper, fabric, staples, scissors and the like. I was making all kinds of stuff: Little books, wallets, bags, pillows, anything I could come up with that was doable with my limited set of tools and materials. I also loved drawing. I had typical toys as well (legos, dolls, playmobil, cars, teddy bears) but the prevailing tendency in my childhood was making stuff. I wasn’t particularly interested in taking things apart to see how they worked, I just liked making new things.

I had never used a computer until I was around 10. We spent Christmas with an uncle of mine and his family in Athens. That uncle was working at Microsoft Hellas, and had a Windows 95 machine in his apartment. I got hooked from the first moment I used that computer. I didn’t do anything particularly interesting in it, just played around with MS Paint and some other equally mundane applications. However, for me it was so fascinating that I spent most of my Christmas vacation that year exploring Windows 95.

After I returned to Lesbos, I knew I badly wanted a computer for myself. However, computers were quite expensive back then, so I didn’t get one immediately, even though my family was quite well off. My father started taking me to his job’s offices on weekends, and I spent hours every time on a Windows 3.1 machine, exploring it, mostly drawing on its paint app.

In 1997, my mother finally bought me a computer. It cost around 700K drachmas (around €2000?) which was much more at the time than it is today. It was a Pentium MMX at 233MHz with 32MB of RAM and a 3.1GB hard drive, which was quite good at the time. I was so looking forward for it to arrive, and when it did, I spent every afternoon using it, from the moment I got back from school, until late at night. The only times I didn’t use my computer was when I was reading computer books or magazines or studying for school. In a year, I had become quite proficient about how its OS worked (Windows 95), editing the registry, trying to learn DOS (its command line). I also exercised my creativity by making magazines and newspapers in Microsoft Word. I’m quite surprised I didn’t break it, even though I was experimenting with anything I could get my cursor on.

Unfortunately, my computer fascination was largely solitary. There were no other geeks in my little town I could relate to, which I guess made me even more of an introvert. The only people reading my MS Word-generated newspaper were me and a friend of mine. During my years in Lesbos, I only met 2 other kinda geeky kids, and we didn’t really hit it off. One of them was living too far, the other was kind of annoying. :P The former however gave me his fonts, which I was really grateful for. I loved fonts. I didn’t have any typographic sophistication, so I loved about every font, but I remember desperately wanting to make my own. Unfortunately, I never pursued that, as I couldn’t find any font creation software until very recently.

In late 1997, we visited some relatives in a NYC suburb to spend Christmas there. It was my first time in the US and I fell in love with the place. My uncle, knowing my computer obsession took me to a big computer store called CompUSA. I was like a kid in a candy store! The software that caught my eye the most was called “Mutimedia Fusion”. It was a graphical IDE that allowed you to make applications (mostly games and screensavers, but you could potentially make anything) without writing any code. The thought processes involved were the same as in programming, but instead of typing commands, you picked them from menus or wrote mathematical expressions through a GUI. You could even go online and get new plugins that added functionality, but my access to the internet in my little town was very limited.

I got super excited. The idea of being able to make my very own programs, was too good to be true. I convinced my mother to buy it for me and thankfully, she did. For the year that followed, my afternoons and weekends became way more creative. I wasn’t interested in making games, but more in utility applications. Things that were going to be useful for my imaginary users. My biggest app back then was something that allowed you to draw different kinds of grids (from horizontal and vertical grids to simple 3d-like kinds of grids), with different parameters, or even mix them together and overlay them over an image. Anything that combined programming with graphics was doubly fascinating for me.

My access to the internet was limited, so I couldn’t share my creations with anybody. What kept me going was the idea that if I make something amazing, it will get popular and people will use it. I had no idea how that would happen, but it was useful as a carrot in front of me that made me constantly strive to improve. We had dial-up, but due to technical issues, I could only connect about 10% of the times I tried it, and even then I had to keep it short as it was quite expensive. I spent my limited time online downloading plugins for Multimedia Fusion, searching anything I could come up with in Altavista and perusing IRC chatrooms with Microsoft Comic Chat.

After a year of making applications with Multimedia Fusion, I wanted something more flexible and powerful. I wanted to finally learn a programming language. My Microsoft uncle sent me a free copy of Visual Studio, so I was trying to decide which “Visual Whatever” language was best to start with. Having read that C++ was “teh pro stuff”, I got a book about Visual C++. Unfortunately, I couldn’t understand much. I decided that it was probably too early for me and C++, so I got a Visual Basic 6 book. It was about 10cm thick, detailing everything you could ever possibly want to learn about Visual Basic. Thankfully, Visual Basic didn’t prove so hard, so I started with it, making small apps and finally ported my grid application from Multimedia Fusion to Visual Basic 6.

I had a very fun and creative 3 years, full of new knowledge and exercise for the mind. Unfortunately, when I reached 15, I realized that boys in my little town weren’t really into geeky girls. I decided that if I wanted a boyfriend, I should quit programming (if any geeky teenage girls are reading this: Just be patient. It gets better, you can’t imagine how much). It “helped” that my computer was broken during the summer and I had to wait for it to come back, so I had to find other things to do in the meantime.

Unable to code, I pursued other geeky interests, such as mobile phones and mathematics, which I guess shows that no matter how much you try, you can’t escape who you are. In retrospect, this helped me, as I got some pretty good distinctions in the various stages of the national mathematical competitions, up to 2nd place nationally for two years in a row (these competitions had 4 stages. I failed the preliminary contest for the Balkan Mathematical Olympiad, so I never went there.). I was fascinated by Number Theory and started wanting to become a mathematician, rather than a programmer. Sometime around then I also moved from my small town to Athens, which I wanted to do since childhood.

When the time of career decisions came, I chickened out. I knew that if I became a mathematician and failed at research, I would end up teaching mathematics in a high school. I didn’t want that, so I picked a “safer” career path. Since my grades were very good, I went to study Electrical and Computer Engineering, which is a profession held in very high esteem in Greece, about as much as lawyers and doctors. I told myself that I would probably find it interesting, as it would involve lots of mathematics and programming. I was wrong.

I was away from Athens, in a city that most Greeks love (Thessaloniki). However, I found it cold, gray, old and with hordes of cockroaches. I hated it with a passion. I also hated my university. It involved little coding and little theoretical Mathematics, the kind that I loved. Most of it was physics and branches of Mathematics I didn’t like, such as linear algebra. It only had two coding courses, both of which were quite mundane and lacked any kind of creativity. Moreover, most of my fellow students had perviously wanted to become doctors and failed medical school so they just went for the next highly respected option. They had no interest in technology and their main life goals were job security, making money and be respected. I felt more lonely than ever. After the first semester, I slowly stopped going to lectures and eventually gave up socializing with them. Not going to lectures is not particularly unusual for a university student in Greece. Most Greeks do it after a while, since attendance is not compulsory and Greek universities are free (as in beer). As long as you pass your exams every semester and do your homework, you can still get a degree just fine.

During my first summer as a university student, we decided with my then boyfriend to make an online forum. We were both big fans of online forums and we wanted to make something better. He set up the forum software in an afternoon (using SMF) and then we started customizing it. I didn’t know much about web development back then, so I constrained myself to helping with images and settings. After 2 months, the forum grew to around 200 members, and we decided to switch to the more professional (and costly) forum software, vBulletin. It was probably too early, but the signs were positive, so we thought better earlier than later.

The migration took 2-3 days of nonstop work, during which we took turns in sleeping and worked the entire time that we were awake. We wanted everything to be perfect, even the forum theme should be as similar to the old one as possible. I had a more involved role in this, and I even started learning a bit of PHP while trying to install some “mods” (modifications to the vBulletin source code that people posted). Due to my programming background, I caught up with it quite easily and after a few months, I was the only one fiddling with code on the website.

I was learning more and more about PHP, HTML, CSS and (later) JavaScript. That online forum was my primary playground, where I put my newly acquired knowledge into practice. Throughout these years, I released quite a few of my own vBulletin mods, many of which are still in use in vBulletin forums worldwide. Having spent so many years making apps that nobody used, I found it fascinating that you can make something and have people use it only a few hours later.

By the end of 2005, I started undertaking some very small scale client work, most (or all) of which doesn’t exist anymore. I was not only interested in code, but also in graphic design. I started buying lots of books, both about the languages involved and graphic design principles. The pace of learning new things back then was crazy, almost on par with my early adolescence years.

In late 2006, I decided I couldn’t take it any more with my university. I had absolutely no interest in Electrical Engineering, and my web development work had consumed me entirely. I didn’t want to give up on higher education, so I tried to decide where I should switch to. Computer Science was the obvious choice, but having grown up with civil engineer parents, I didn’t want to give up on engineering just yet (strangely, CS is not considered engineering in Greece, it’s considered a science, kinda like Mathematics). I also loved graphic design, so I considered going to a graphic design school, but there are no respected graphic design universities in Greece and I wasn’t ready to study abroad. I was also in a long term relationship in Greece, which I didn’t want to give up on.

I decided to go with Architecture, although I had no interest in buildings. The idea was that it bridges engineering and art, so it would satisfy both of my interests. Unfortunately, since I hadn’t taken drawing classes in high school, I had to take the entire national university placement exams (Πανελλήνιες), again, including courses I aced the first time, such as Mathematics. I was supposed to spend the first half of 2007 preparing for these exams, but instead I spent most of it freelancing and learning more about web development. I did quite well on the courses I had been previously examined on (although not as good as the first time), but borderline failed freehand drawing. Passing freehand drawing was a requirement for Architecture, so that was out of the question now. This seemed like a disaster at the time, but in retrospect, I’m very grateful to the grader that failed me. I would’ve been utterly miserable in Architecture.

Not wanting to go back to EE, I took a look at my options. My mother suggested Computer Science and even though I was still a bit reluctant, I put it in my application. I picked a CS school that seemed more programming-oriented, as I didn’t want to have many physics, computer architecture and circuits courses again. When the results came out, I had been placed there. It turned out to be one of my best decisions. I could get good grades on most of the courses with hardly any studying, as I knew lots of the stuff already. I also learned a bunch of useful new things. I can’t say that everything I learned was useful for my work, but it was enough to make it worth it.

In mid 2007, the online forum we built had grown quite a lot. We decided to make a company around it, in order to be able to accept more high-end advertising. We had many dreams about expanding what it does, most of which never got materialized. In 2008, after a long time of back and forth, we officially registered a company for it so I stopped freelancing and focused solely on that.

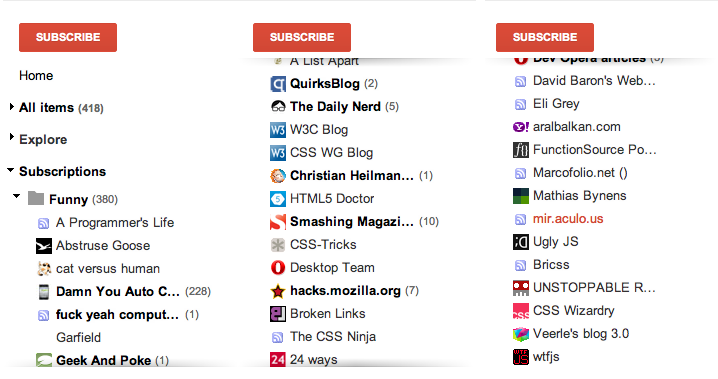

It wasn’t easy, but eventually it started generating a very moderate income. I decided to start a Greek blog to post about my CSS and JS discoveries, but it didn’t go very well. After a dozen posts or so, I decided to close it down, and start a new one, in English this time. It turned out that developers abroad were more interested in what I had to say, so I got my first conference invitation in 2010, to speak in a new Polish conference called Front-Trends. When I got the invitation email, I couldn’t believe my eyes. Why would someone want me to speak at a conference? I wasn’t that good! How would I speak in front of all these people? It even crossed my mind that it might be a joke, but they had confirmed speakers like Douglas Crockford, Jake Archibald, Jeremy Keith and Paul Bakaus. I told my inner shy self to shut up, and enthusiastically agreed to speak there.

I spent the 8 months until that conference stressing about my presentation. I had never been to a conference outside Greece, and the only Greek conference I had attended was a graphic design one. I had only spoken once before, to an audience of around 30 people in a barcamp-style event. I decided that I didn’t want my first web development conference to be the one I speak at, so I bought a ticket for Fronteers 2010. It had a great line-up and was quite affordable (less than €300 for a ticket). I convinced 3 of my friends to come with me (for vacation), and we shared a quadruple hotel room, so the accommodation ended up not costing too much either.

It was an amazing experience that I will never forget. I met people I admired and only knew through their work online. It was the first time in my life that I was face to face with people that really shared the same interests. I even met my partner to date there. Until today, Fronteers is my favorite conference. Partly because it was my first, partly because it’s a truly great conference with a very strong sense of community.

There was a talk or two at Fronteers that year, which were criticized for showing things that most people in the audience already knew. This became my worst fear about giving talks. Until today, I always try to add nuggets of more advanced techniques in my talks, to avoid getting that kind of reaction, and it works quite well. I remember going back home after Fronteers and pretty much changing all my slides for my upcoming talk. I trashed my death-by-powerpoint kind of slides and my neat bulleted lists and made a web-based slideshow with interactive examples for everything I wanted to show.

I was incredibly nervous before and during my Front-Trends talk, so I kept mumbling and confusing my words. However, despite what I thought throughout, the crowd there loved it. The comments on twitter were enthusiastic! Many people even said it was the best talk of the conference.

That first talk was the beginning of a roller-coaster that I just can’t describe. I started getting more invitations for talks, articles, workshops and many other kinds of fascinating things. I met amazing people along the way. Funny, like-minded, intelligent people. To this day, I think that getting in this industry has been the best thing in my life. I have experienced no sexism or other discrimination, nothing negative, just pure fun, creativity and a sense that I belong in a community with like-minded people that understand me. It’s been great, and I hope it continues to be like this for a very long time. Thank you all.